Oil Industry’s Toxic Waste Crisis: Trillions of Gallons Buried Underground

A Century of Concerns About Injection Wells

A cache of government documents spanning nearly a century has raised serious questions about the safety of the oil and gas industry’s primary method for disposing of its annual trillion gallons of toxic wastewater: injecting it deep underground. These records reveal that by the early 1970s, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was aware that injection wells were merely a temporary solution, meant to be used only until a more environmentally sound disposal method became available.

The documents, which include scientific research, internal communications, and talks from a 1971 symposium involving industry and government representatives, come from multiple federal agencies such as the EPA, the U.S. Department of Energy, and the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). They suggest that there may be little scientific basis for claims that injection wells are safe, putting drinking water and other natural resources at risk across the country.

The U.S. oil and gas industry generates an astonishing 25.9 billion barrels of wastewater annually—equivalent to 1.0878 trillion gallons. This waste is often referred to as “produced water,” “brine,” or “salt water.” Approximately 96% of this wastewater is disposed of by injecting it back into the ground. In 2020, there were 181,431 injection wells in the United States, with roughly 11 per Starbucks location. If lined along a highway from New York City to Los Angeles, an injection well would appear every nine-tenths of a second.

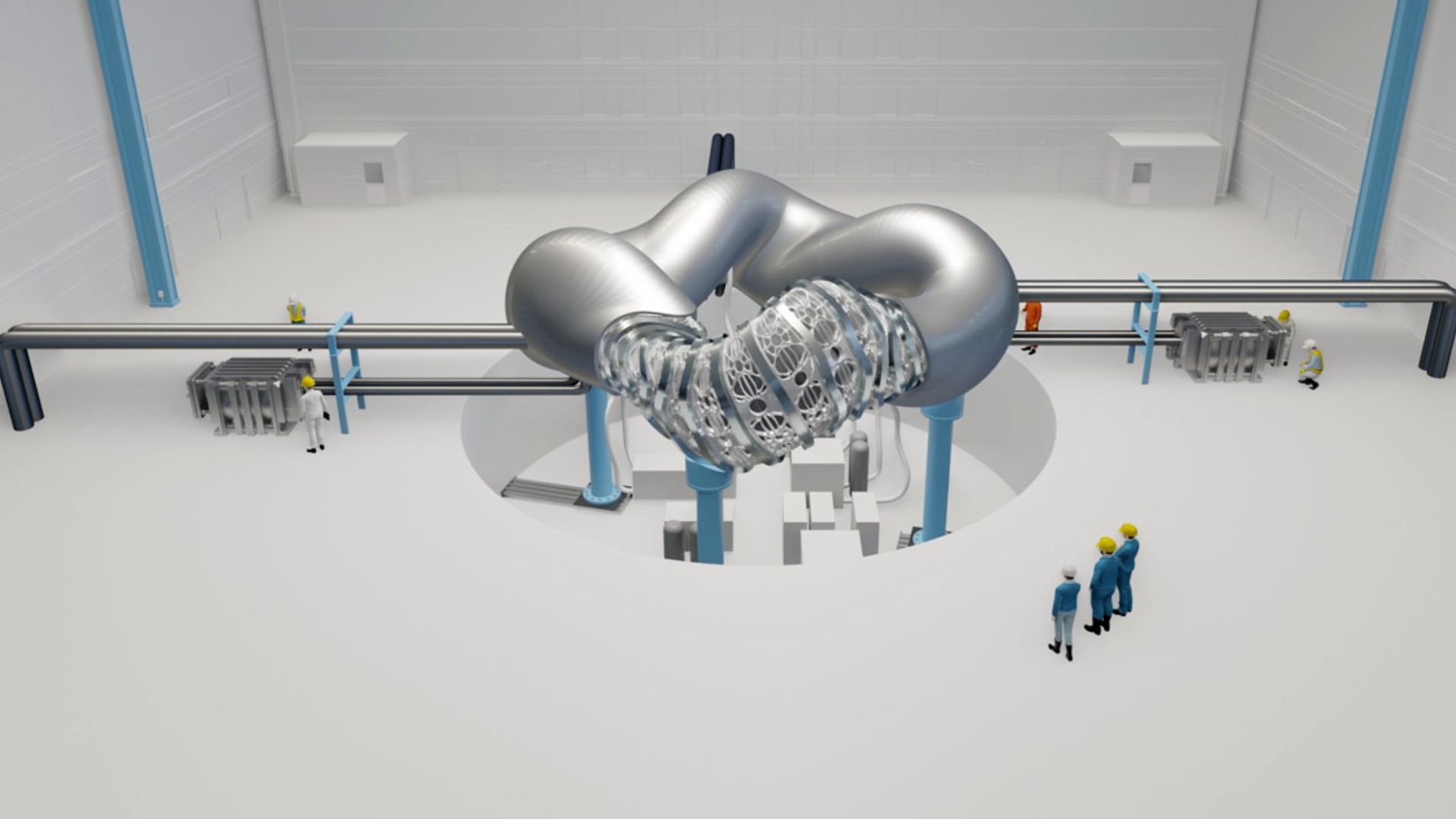

These injection wells operate by forcing wastewater deep underground into rock formations with pore spaces where the waste can accumulate. However, the wastewater often contains high levels of salt, carcinogens, heavy metals, and radioactive elements like radium. Radium, known as a “bone-seeker,” has been linked to severe health effects, including those suffered by the Radium Girls in the early 20th century.

Early Warnings and Persistent Risks

Wastewater has long been a problem for the petroleum industry, dating back to its origins in western Pennsylvania over 150 years ago. Initially, drillers dumped wastewater into pits or streams, sometimes even using them as swimming pools. By the mid-20th century, the industry began using injection wells not just for disposal but also for enhanced oil recovery, pushing hard-to-reach oil to the surface.

The Clean Water Act of 1972 forced industries to stop dumping waste into rivers, leading to a surge in underground disposal. Despite concerns raised by scientists and regulators, the use of injection wells continued to grow. In 1971, during a symposium on underground waste management, experts warned of potential risks, including earthquakes, groundwater contamination, and the long-term unpredictability of injected waste.

One USGS hydrologist, John Ferris, noted that no rock is completely impermeable, and wastewater could eventually escape the injection zone, spreading to water sources and other areas. Another geologist, Orlo Childs, asked, “Where will the waste reside 100 years from now?” His question remains unanswered today.

Regulatory Challenges and Industry Pushback

In 1980, the EPA began regulating injection wells under the Underground Injection Control (UIC) program. However, industry pushback led to weakened regulations, allowing states to take control of oversight. Today, 33 states regulate injection wells, including Ohio, Texas, and Oklahoma.

Despite these changes, concerns about the environmental impact of injection wells persist. A 1987 EPA report highlighted the difficulty of predicting the fate of injected waste, noting that subsurface environments often take years to reach equilibrium. Another report warned of the potential for waste to escape through fractures, corroded wells, or old oil and gas wells, contaminating groundwater.

The rise of fracking in the early 2000s has further increased the volume of wastewater, much of which ends up in injection wells. The chemicals used in fracking are designed to fracture rock, but their long-term effects in underground environments remain largely unknown.

Legal Battles and Environmental Threats

Recent lawsuits and environmental incidents highlight the growing risks associated with injection wells. In Ohio, a landowner sued injection well operators, alleging contamination of his property and oil wells. In Oklahoma, ProPublica and Frontier reported on “purges” where wastewater injected at high pressure cracked underground rock, causing uncontrolled leaks. In West Texas, “zombie wells” have spewed toxic waste, creating environmental hazards.

Satellite data from a 2024 study showed that excessive wastewater injection has raised land in parts of the Permian Basin, increasing the risk of blowouts. Meanwhile, advocacy groups argue that the lack of regulation allows the oil and gas industry to dispose of waste cheaply, endangering public health and the environment.

Industry Defenses and Ongoing Debates

The American Petroleum Institute (API) continues to defend injection wells as safe and essential for the industry. However, critics argue that the practice poses significant long-term risks. As the debate continues, the legacy of decades-old warnings about injection wells remains a pressing issue for communities, regulators, and the environment.

- 100 Soal dan Kunci Jawaban IPAS SD Kelas 2 Semester 2 Kurikulum Merdeka 2026 - March 7, 2026

- Membentuk Karakter Bangsa: Dandim 0605 Subang Tekankan Pentingnya Mendengar dan Menghargai - March 7, 2026

- Hukum Natalie: Pengakap Perempuan Sacramento Mengatasi Bahaya Panas Ekstrem bagi Anak-anak California - March 7, 2026

Leave a Reply