World’s largest fusion reactor shuts for 3 years after $660M debut

The world’s newest flagship fusion machine has barely finished proving it can work, and already it is heading into a long pause. After a high profile debut campaign that cost hundreds of millions of dollars, the JT-60SA reactor in Japan is preparing for a multi year shutdown so engineers can transform it from a proof of concept device into a fully equipped workhorse for fusion science. The move underscores how fusion’s biggest projects are now running on a generational clock, where each experimental step is expensive, slow, and strategically choreographed rather than a straight sprint to commercial power.

The planned hiatus is not a sign of failure so much as a reminder that the world’s largest operational superconducting tokamak is still a prototype, and that the path to practical fusion power is measured in upgrades, not headlines. As researchers pivot from celebrating first plasma to reconfiguring hardware, the stakes are clear: what happens inside this three year window will shape how quickly fusion can move from “dream power” to a realistic pillar of the global energy system.

JT-60SA’s rapid rise to the top of fusion research

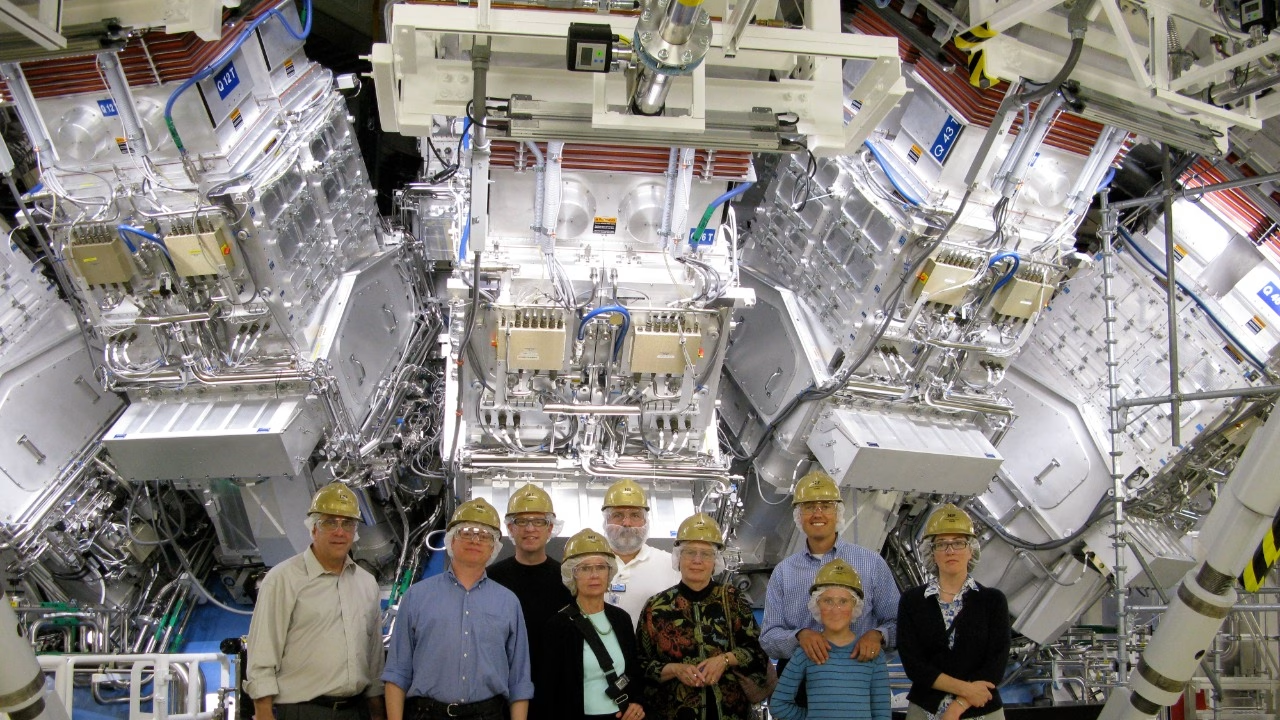

JT-60SA vaulted into prominence when it achieved first plasma and was declared active, instantly becoming the largest operational superconducting tokamak on the planet. Built in Japan as a joint project with European partners, the machine is designed as a bridge between earlier national reactors and the coming generation of international megaprojects. According to project documentation, JT-60SA achieved first plasma on October 23, 2023 and was declared active on December 1, 2023, a compressed timeline that gave scientists a rare chance to test a brand new superconducting device at full scale.The machine’s scale and technology have made it a magnet for advanced research partnerships. They ( NTT and QST ) have already tested their ( NTT and QST ) research on JT-60SA, a massive tokamak in Japan developed jointly by Japan and the European Union, using the reactor as a proving ground for new control and diagnostic techniques. That early wave of experiments helped confirm that the core systems behave as designed, which is precisely what the initial campaign was meant to establish before any long shutdown was even on the table.

Why the “world’s largest” fusion machine is pausing so soon

The decision to halt operations for several years so soon after activation reflects how carefully staged modern fusion programs have become. With the first campaign complete, project leaders now have enough data to justify opening the machine back up, installing new components, and reconfiguring systems that could not be finalized before first plasma. European project material notes that with confirmation that JT-60SA’s core systems work, the reactor will enter a planned shutdown for two to three years while new equipment is added and other ones are upgraded. That pause is not an emergency stop, it is a scheduled transition from a shakedown machine into a fully instrumented physics facility.The price tag attached to this early phase, roughly $660 million when converted from the project’s reported budgets, underlines how much is riding on getting the upgrade sequence right. A long shutdown at this stage allows engineers to integrate more sophisticated heating systems, diagnostics, and control hardware without the pressure of keeping a continuous experimental schedule. In practice, that means the world’s largest operational superconducting tokamak will spend much of its early life offline, but the payoff is a reactor that can run more complex and higher power scenarios once it returns, rather than limping along with a half finished toolkit.

How JT-60SA fits into a global fusion ecosystem

JT-60SA is not an isolated experiment, it is one node in a dense global network of fusion devices that now numbers in the triple digits. International planning documents describe how Upon completion of the main reactor and first plasma, planned for 2033–2034, ITER will be the largest of more than 100 fusion reactors built since the 1950s, and JT-60SA is explicitly designed to feed into that ecosystem. Its superconducting magnets, plasma shaping, and control strategies are all tuned to explore regimes that will be directly relevant for the next generation of machines.That global context is why the shutdown matters beyond Japan. The international ITER project in southern France, for example, depends on partner devices to test operating scenarios and technologies before they are locked into its own hardware. JT-60SA’s pause for upgrades is therefore not just a local engineering decision, it is a coordinated move in a broader choreography where each reactor takes turns pushing the frontier while others retool. When JT-60SA comes back online, it will be expected to shoulder a larger share of that experimental load, especially in regimes that smaller national machines cannot reach.

ITER’s stretched timeline and what it means for JT-60SA

The long break at JT-60SA also has to be read against the shifting schedule of the world’s biggest fusion construction site. Over the summer, project managers acknowledged that the ITER fusion reactor to see further delays, with operations pushed to 2034 and full fusion power not expected until nearly 2040 on new timeline. That slippage effectively extends the window in which supporting machines like JT-60SA will be the main platforms for high end tokamak research.From a planning perspective, the delay gives JT-60SA’s team more breathing room to take the reactor offline now and still deliver valuable data before ITER reaches its own first plasma. The Japanese European machine can spend two to three years in pieces, then return with upgraded systems that are better aligned with ITER’s revised schedule. In that sense, the shutdown is less a setback and more a recalibration, ensuring that when ITER finally starts operating at scale, it will be able to draw on a decade of experience from a fully matured superconducting tokamak that has already explored many of the same operating regimes.

Lessons from JET’s 40 year run and Brexit era politics

The decision to invest in a long upgrade pause at JT-60SA is shaped by the legacy of earlier European machines, especially the Joint European Torus. The Joint European Torus (JET) facility delivered major nuclear fusion milestones over 40 years of operation before finally shutting down, proving that a single reactor can anchor a continent’s fusion program for decades if it is upgraded and maintained strategically. JET’s final campaigns set new records for sustained fusion energy, but they also highlighted how difficult it is to keep an aging machine competitive once its original design envelope has been exhausted.Political turbulence added another layer of complexity. As the United Kingdom moved through the Brexit process, talks over JET’s future were put on hold, then revived when the UK Government and European Commission signed new arrangements that allowed operations to continue. That experience left European fusion planners acutely aware that long lived reactors are vulnerable not just to technical obsolescence but to shifting political frameworks. JT-60SA’s more front loaded upgrade strategy, with a major shutdown early in its life, is one way to lock in capabilities before external factors can erode support for incremental improvements later on.

“Dream power” and the 70 year chase for fusion energy

Behind the engineering schedules and budget lines sits a much older narrative about why fusion matters at all. Advocates have long described it as a kind of idealized energy source, one that could deliver vast power with minimal long lived waste and no carbon emissions. As one detailed overview puts it, Why Fusion Energy Is the ‘Dream Power’ the World Has Chased for 70 Years, Shohei Nagatsuji March explains how this Dream Power the World Has Chased for Years offers several advantages over conventional reactors, from safety characteristics to fuel abundance.That 70 year pursuit is precisely why a three year shutdown at JT-60SA can feel both frustrating and oddly routine. On the one hand, the world is facing urgent climate and energy security pressures that make any delay in deploying low carbon power sources feel costly. On the other, fusion has always been a multi decade project, and the current generation of machines is still squarely in the experimental phase. In that context, pausing a newly active reactor to install better tools is less a detour than a necessary step in turning a long running scientific dream into something that can eventually compete with real world power plants.

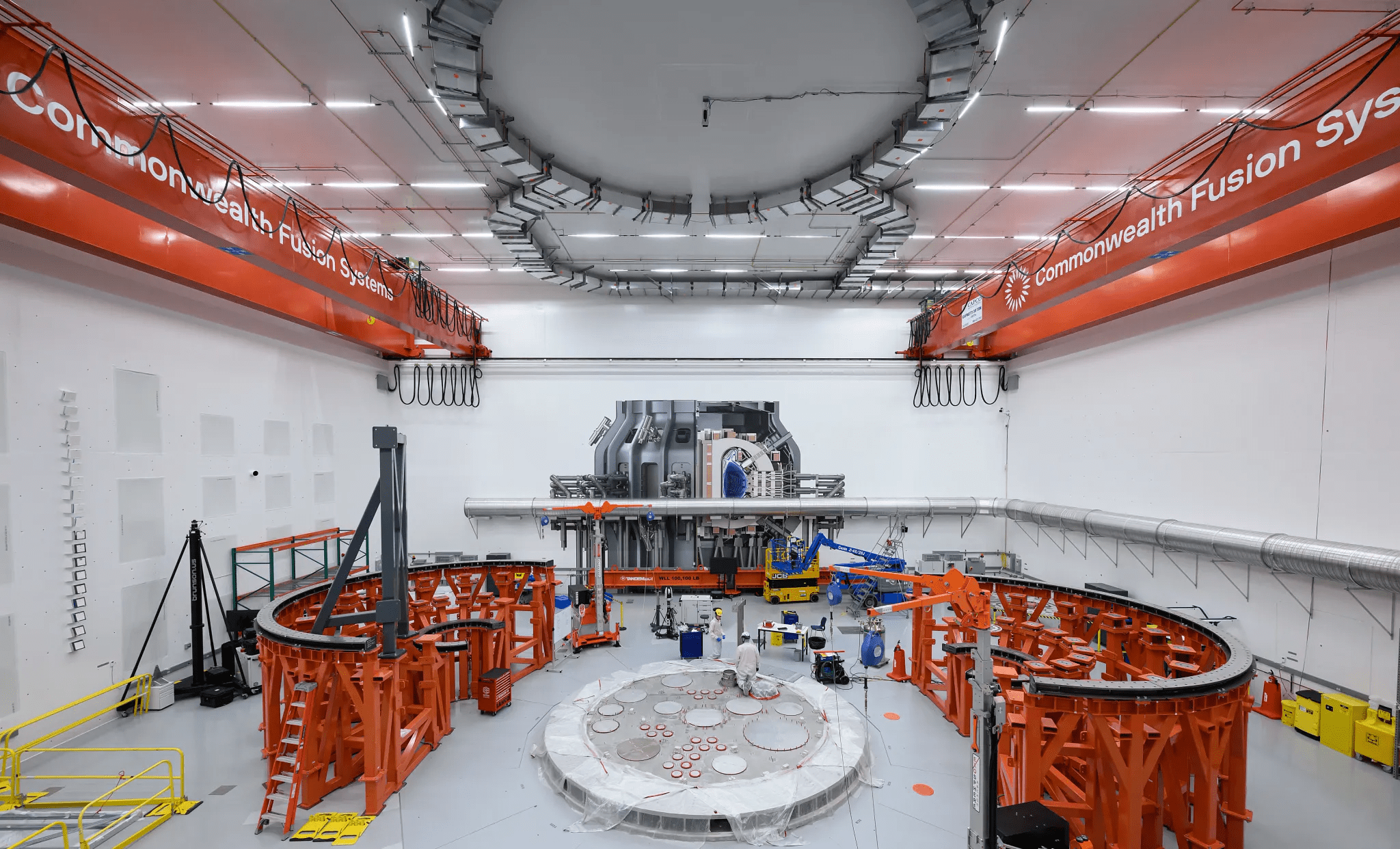

Big science, big budgets, and the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment parallel

The financial scale of JT-60SA’s early operations and upgrades places it firmly in the club of “big science” facilities that must justify their costs over many years. That club includes projects far outside fusion, such as the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment in the United States. Planning documents for that effort note that The CD-1RR process was completed with an estimated cost for the project of $3.3 billion and an upper allowed cost range that reflects the possibility that some planned components may not ever be constructed, a reminder that even well funded experiments must constantly adapt to budget and scope pressures.

Fusion reactors like JT-60SA operate under similar constraints, albeit with different technical goals. The roughly $660 million invested in its initial build and commissioning is only the opening bid in a long series of funding decisions that will determine how much of its original vision is realized. The planned multi year shutdown is therefore not just a technical maneuver, it is a financial and political bet that front loading upgrades will make the reactor more valuable to international partners and national governments over the long term, in much the same way that neutrino facilities have had to stage their construction and operations to stay viable.

From first plasma to full campaigns: JT-60SA’s upgrade roadmap

Technically, the pause at JT-60SA marks the transition from a commissioning phase focused on basic plasma production to a more ambitious program aimed at high performance operation. Engineering summaries emphasize that VII CONCLUSION JT-60SA operation restarted and the first tokamak plasma is expected in 2023, Following this, operation will expand as additional systems come online, outlining a roadmap in which each new subsystem unlocks more demanding experimental scenarios. The upcoming shutdown is the moment when many of those additional systems can finally be installed and integrated without the constraints of day to day experimental schedules.In practice, that means the reactor’s next life will look very different from its first. Once the new equipment is in place, JT-60SA will be able to run longer pulses, explore more aggressive plasma shapes, and test control strategies that are directly relevant for devices like ITER. The early first plasma shots were about proving that the magnets, vacuum vessel, and basic control systems worked. The post upgrade campaigns will be about pushing the machine to its design limits, a shift that justifies the disruption of taking the world’s largest operational superconducting tokamak offline for several years at a critical moment in fusion research.

What a three year pause means for the fusion race

For all the strategic logic behind the shutdown, there is no escaping the optics of seeing a flagship reactor go dark so soon after its debut. Critics of fusion often point to such pauses as evidence that the field is perpetually stuck in prototype mode, always promising breakthroughs just over the horizon. Supporters counter that the current generation of machines is finally large and sophisticated enough to generate data that can feed directly into reactor scale designs, and that taking the time to upgrade them properly is a sign of maturity rather than drift.

On balance, the JT-60SA pause looks less like a retreat and more like a calculated reset. By aligning its upgrade window with ITER’s delayed schedule, leveraging partnerships with groups like NTT and QST, and building on lessons from JET’s 40 year arc and the broader 70 year chase for fusion’s Dream Power, the project is trying to ensure that its next operational phase delivers maximum scientific and strategic value. The world’s largest operational superconducting tokamak may be quiet for the next few years, but the choices made during that silence will echo across the fusion landscape for decades.

More from Bisakimia

Leave a Reply